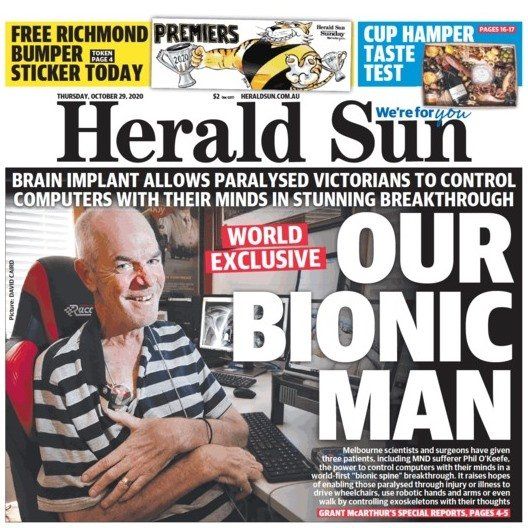

‘Bionic Spine’ Breakthrough Brings Hope to the Disabled

Grant McArthur, Herald Sun

October 28, 2020 10:00pm

Melbourne scientists and surgeons have given patients with disabilities the power to work computers with their mind in a world-first “bionic spine” breakthrough.

The stunning success, revealed for the first time today, raises hopes of giving those paralysed though injury or illness the ability to drive wheelchairs, use robotic hands and arms or even walk by controlling future exoskeletons with their thoughts.

During pioneering non-invasive procedures, three Victorians with conditions such as motor neurone disease were each fitted with a paperclip-sized implant to the centre of their brain, which can translate and transmit their brain signals directly to a computer.

The University of Melbourne and Royal Melbourne Hospital Stentrode implants are also allowing the patients to use mobile phones, however principal investigator Professor Peter Mitchell said the sky was the limit now they had proved the ability to translate thought into action.

“It has exceeded what we had hoped for and what the aim of the original study was,” Prof Mitchell said.

Race is on for the keys to Town Hall

“The limits of what can be achieved, we just don’t know. Once you get that signal out, and once you start to learn how to modulate that signal, I suspect the way that signal can be used will just expand.

“At the moment it is just interfacing with a standard operating system on a computer, but there’s no reason it can’t go well beyond that.

“Anything that you can imagine you can do with your phone or your computer I think you will be able to do with this device — be that moving a wheelchair, be that driving a robotic arm.”

Royal Melbourne Hospital lead researchers Dr Tom Oxley and Dr Nick Opie.

Photo: David Caird

The first Stentrode implant was fitted into the brain of Graham Felstead, 75, from Victoria in August 2019. He is still using the technology and is doing extremely well.

Prof Mitchell and his RMH team implanted the second into Greendale father Phil O’Keefe in April.

A third patient has since undergone the procedure as part of an initital five-patient safety trial, however the full results are not yet available.

Rather than requiring invasive brain surgery, a catheter was used to thread the 8mm x 40mm implants up the patients’ jugular vein and into their skull, where it is passed along main draining vein running from the front to the back of their brain.

Once in place, the self-expanding implant is fixed above the motor cortex - the area that controls movement - where its 16 sensors connect to locations responsible for different actions.

A lead passing down the back of the skull connects the Stentrode to a recorder implanted near the patient’s collar bone, which transmits brain signals wirelessly using infra-red light to a control unit which can be connected to a computer or other electronic device.

While the initial trial was only intended to determine if the device was safe to place in a human brain - rather than whether they actually worked - results published in the Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery overnight reveal the first procedures have been far more successful than the Melbourne team ever hoped.

Associate Professor Nicholas Opie, head of the University’s Vascular Bionics Laboratory and creator of the device, said the implants were already allowing patients to send emails and complete online banking and shopping.

“It has been a long process, but to now start seeing the fruits of the labour and to see the guys using it to enhance their lives has been really magical,” Prof Opie said.

“We are engineers, we know that what we make is going to work but to actually see it help somebody is what we are all about.”

Although all 16 sensors of the implanted Stentrodes are successfully transmitting signals from different parts of the mens’ brains, the researchers are currently only harnessing information from one sensor which enables the participants to undertake basic tasks.

As the technology develops, the team plans to utilise signals from more sensors, which can be used in combination with multiple switches in different orders to complete increasingly complex actions.

“Getting the signals out is pretty straightforward. The challenge and opportunity is how do we translate what the signals are into something that can be meaningful?” Assoc Prof Opie said.

“The hardware does not need to be different, but we will make more use of the brain activity to allow for different movements or commands.”

The technology, the brainchild of RMH neurologist Dr Tom Oxley, was initially funded by the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

It is now also backed by the Australian Government which in June awarded a $1.48 million grant for a second expanded trial, involving the University’s licensed commercialization partner Synchron Australia.

After the current five-patient trial is completed in the first quarter of 2021, the second phase of testing is expected to see a further 10-15 patients implanted with the technology across Australia.

Previous international efforts to develop a bionic spine have involved highly invasive procedures where patient’s skulls are removed to allow electrodes to be placed in the top of their brain and leads connecting to hardware outside of the skin.

The Melbourne team now plans to determine if the same success can be replicated in a larger study before any attempts are made to link their signalling process to further computer systems or robotic limbs, which are still in the early phase of development and not yet ready for human use.

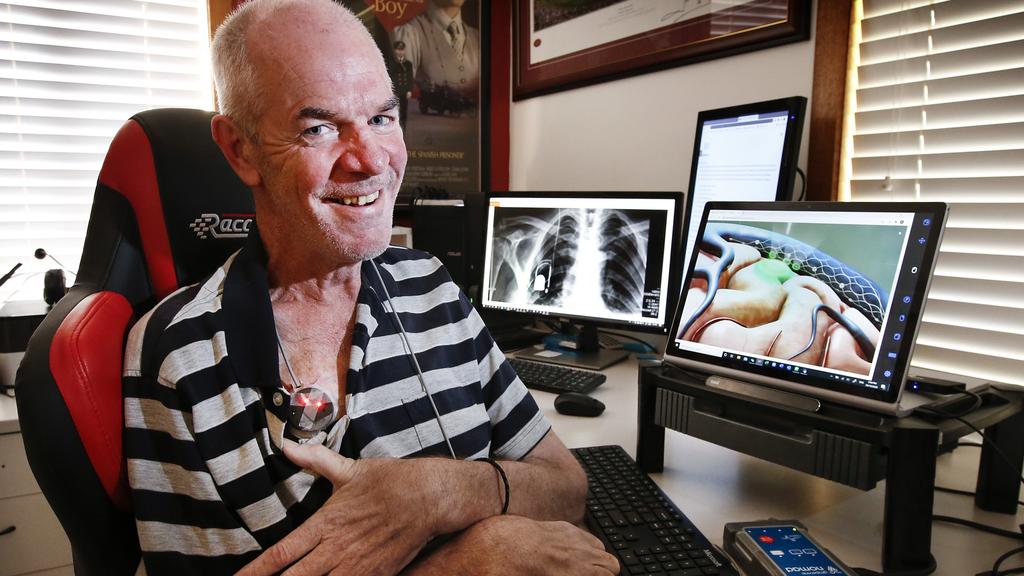

MND sufferer Phil O'Keefe is the second person to undergo the Stentrode implant and is now able to use his thoughts to work a computer.

Photo: David Caird

MELBOURNE DAD’S LIFE IMPROVED BY STENTRODE IMPLANT

Phil O’Keefe’s hands, arms and even breath are starting to fail, but he is determined to push his brain as far as he can — even if that means pushing the boundaries of science in the process.

After becoming just the second person in the world fitted with an experimental Stentrode implant in April, the father of two is honing his skills to type emails and communicate in defiance of worsening motor neurone disease.

Through a combination of eye-tracking technology and electrical signals transmitted directly from his brain to his computer, Mr O’Keefe can type messages or surf the net without moving a muscle.

But the 60-year-old wants to drive the technology further. He dreams of having his Greendale home fitted with smart devices so he can control the world around him while laying a foundation for others to gain far more in the coming years.

“There is no doubt that we are pioneers,” Mr O’Keefe said.

“I am proof it works — the trick now is to make it as efficient as it can be.

“I sent an email a few weeks ago and it took me about 20 minutes to do. But the next time I did it, it took me about five minutes. You have to train your brain to be that efficient all the time.

“Any Bluetooth device should be able to be controlled by this technology. so why can’t I modify my home and put smart switches on the lights and the power points? If the kids are annoying me I can just turn the TV on and off.

“The limitations on this technology are only controlled by your imagination.

“There is nothing to say that, for people who are paralysed, they can’t embed a device into their limbs so they think (and) move their arms again.

“Maybe in the future — five years or 10 years — you will be able to lift your arm and grab a cup of coffee and have a drink of it safely.”

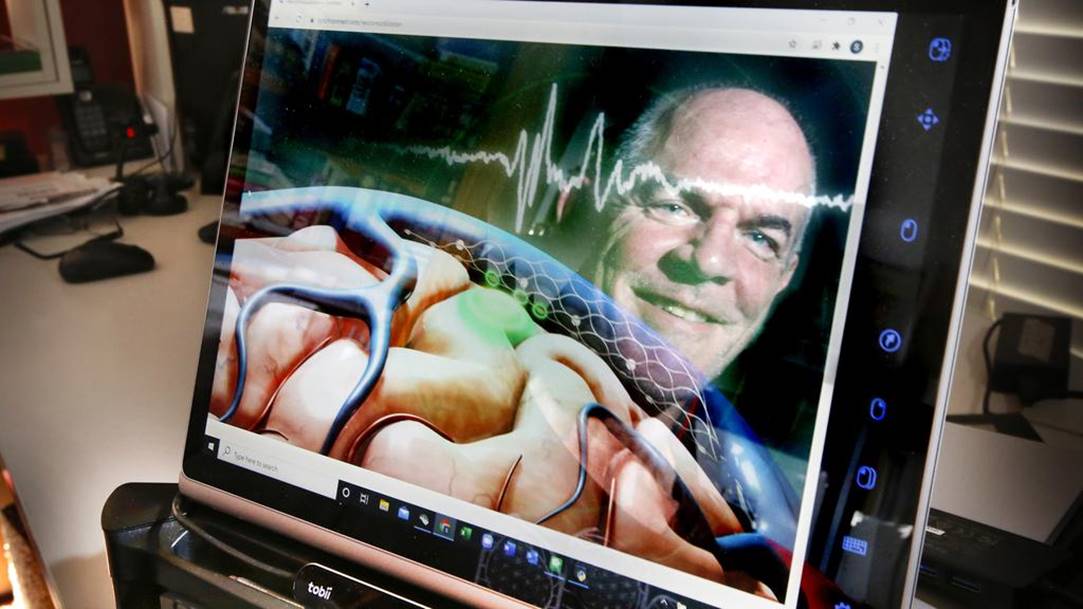

Phil looks at an image of the implanted electrode that sits in the vein of his brain.

Photo: David Caird

As well as the undergoing the implant procedure, Mr O’Keefe is taking part in brain training to develop his abilities.

By asking him to think about movements such as clenching his fist, tapping his foot or bending his knee, the scientists can determine which functions of his brain transmit the strongest signals.

Those signals are then used as a switch, so when Mr O’Keefe’s computer cursor sits over an app on the screen, he can think, for example, “move left leg” and activate it. As time goes on, the thought process should become more natural and happen almost unconsciously.

Having had MND slowly progress to impact his upper arms, his respiratory function, his back and neck and now the hand fine motor skills needed to write or use a keyboard, Mr O’Keefe is determined to harness his mind instead.

“They gave me a life expectancy of five years (but) I’ve got to five and a half and I’m still here,” he said.

“I have lost the ability to communicate with the outside world in an efficient manner.

“It’s incredibly difficult. This disease takes away your physical ability but it leaves your mind fully cognisant of what’s going on.

“It is emotionally draining and intellectually challenging.

“When I do lose the ability to talk and my hands seize up on me, I will just be able to have somebody hook me up to this computer and I can go through all my emails, send emails to various people - delete the ones I don’t want to talk to - read the news on the news websites, just keep in touch...I see the future benefits for people as unlimited.

“I would be lost without this physically and totally lost emotionally.

“It gives me a great sense of satisfaction when I do things on my own and gives me a great sense of satisfaction when the professors come out and we have a session and they walk away with a whole new set of ideas in their head.”

more articles on stentrode

University of Melbourne | Translating Thought Into Action

3AW | Melbourne research enables paralysed people to control a computer with their thoughts

ABC Radio Melbourne | 'Bionic spine' breakthrough allows patients to control computers with their mind

Wall Street Journal | Tiny Brain Implants Hold Big Promise for Immobilized Patients

The Royal Melbourne Hospital Neuroscience Foundation

RMH Neuroscience Foundation

PO Box 2116

Royal Melbourne Hospital VIC 3050

In the spirit of reconciliation, the Royal Melbourne Hospital Neuroscience Foundation acknowledges the Kulin nations as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which our services are located. We are committed to improving the health and well-being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, as with all Australians.